All

about the Cynon Valley

The

eastern sky is lightening behind the Abercynon Ridgeway which is silhouetted

with startling clarity against that luminous backdrop. The valley is awakening,

traffic is humming and the dawn chorus provides a melodic accompaniment for

the new day. We move back in time to another sunrise - a billion years ago.

Earth's crust is buckling under tectonic pressure. The strata of the earth,

layered one above the other, are shifted and misaligned so that the tropical

forests of the Carboniferous era rise close to the surface at what, in an

unimaginable future, will be one of the valleys of South Wales.

Time

passes.......

Storm and ice-cloud darken the primeval sky and the landscape is being contorted

by the weight of ice. The age of wind, ice and snow is shaping the land. Atop

an upward fold of rock a glacier is forming. Over the millennia it grows,

forcing open, eroding the rocks and over the millennia it retreats as the

ice age ends, leaving behind it a river in a broad valley, fertile with glacial

deposits.

Trees

are growing across this valley floor and coating the mountains' sides; oak,

birch and ash. The river's banks are becoming edged with glossy green alder

as it widens its bed, meandering through the seventy square miles of valley

and out over the south-eastern plains.

Time passes.

Man moves into the valley and clears land for cottages and for crops and animal

grazing. The woods are still growing dense and lush. There is plenty of rain,

brought in to the valley from the ocean over the summit of the glacial cwm

where birds are wheeling high in a wild sky.

Cistercian monks are treading a path over the mountains in order to bring

to the valley knowledge of Christianity and sheep and beer. In a wood-girdled

clearing close to the riverside, the Church of St John the Baptist is built

at the end of the first millennium.

Little villages are forming and hill farmers are clearing larger areas of

woodland for their sheep to graze. The villages extend from Penderyn and Hirwaun

in the north west to Ynysybwl and Abercynon in the south east, where the Cynon

meets the larger Taff.

are discovered - as coal. Lives and landscape are beginning to change. Men are sinking

primitive shafts or digging into the sides of the mountains to extract this fuel.

Many of the valley people are beginning to exist in a half-life, spending long hours

beneath the ground in dark and danger, all for warmth in the hearth.

Now, with a grinding clank of machinery and a sky dark again with smoke, is coming

the Industrial Revolution and the landscape of Cynon Valley is undergoing an even

more drastic change. First iron and then coal are becoming the new gold, making

kings of landowners and troglodytes of the workers. There are ships and trains

to be fuelled, cities to be kept warm, the furnaces of industry to be fed: Britannia and her colonies are looking to the valleys of Wales for their fires.

In 1804 the village of Abercynon becomes the end of the line for Richard Trevithick's famous locomotive which brings iron from the foundries at Merthyr Tydfil to be loaded onto barges on the Glamorgan Canal in Abercynon for passage to the port of Cardiff.

At Gadlys, Llwydcoed and Abernant, the iron furnaces are flourishing, as they are all through the valleys. Seen from the village of Hirwaun the north-eastern night sky glows red from the furnaces of Crawshay's giant foundries in Merthyr Tydfil. Railways criss-cross the smoking valley, the air resounds with the clang of metal, of trains against buffers, of sirens summoning men to work: it is the groaning of a vital cog in a great machine.

The iron industry is beginning to decline and coal mining is on the upsurge. 1842 - the first ironworks in Hirwaun has closed. A few years later the pits of Cynon Valley are producing well over two million tons of coal a year. Mine shafts drive deep into the earth and people and ponies are dying in droves when fire-damp ignites, roofs fall in and explosions tear through the mines' narrow tunnels . Coal waste is being tipped on adjacent land, obscene black growths smothering any remaining green.

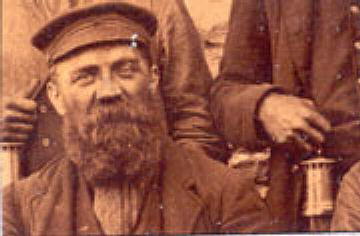

At the coal industry's peak, men are living and dying for this black gold, their bodies tattooed with, their lungs sucking in, the fine, glittering dust. Man and coal become as one. In the valley of the smaller river Dare alone, within Cynon Valley, there are no less than nineteen deep and drift mines.

It is as if the land has been turned inside out. Everywhere there is blackness and the gleam of rails like arteries winding over the valley floor, supported sometimes by huge wooden viaducts straddling hills, carrying the black life-blood of the valley.

Houses of sorts are going up throughout Cynon Valley for the Irish, Polish and Italian immigrants who are pouring into this and other valleys, lured by the promise of work in the mines.

Some housing is reasonable, some less so: Greenfach, for example, close to the Gadlys pit in Aberdare, where the row of houses fronting the river Dare is a no-go area for anyone except its inhabitants and the rats.

Workmen's Halls are being built. These grand edifices hold books and knowledge and provide a meeting place other than the public houses that are sitting at every twist and turn of the valley's narrow streets.

A blacksmith called Griffith Rhys Jones - Caradog - leads the South Wales Choral Union to victory both in 1872 and 1873 in the Crystal Palace Cup competition.|

At

Trecynon, Aberdare Park is created,

with its marvellous arboretum, boating lake, bandstand, and eventually paddling

pool and children's playground.

Chapels are springing up all through the valley, nearly as plentiful as the

public houses and it is a close thing which of the two has the better attendance.

There are the Calfarias, Noddfas, Siloas and Trinitys and they are usually

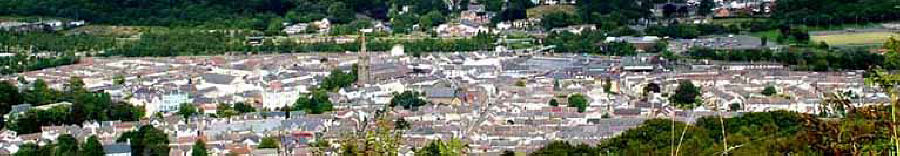

packed morning noon and evening on Sundays. A spire is now rising above Aberdare

as the church of St Elvan becomes the centrepiece of the town.

1913 - the fortunes of the coal industry is at its zenith. Steam and anthracite coal is being exported all around the world.

In Abercwmboi, the Phurnacite plant thrusts its spires skywards but these chimneys are belching out black smoke day and night to create the smokeless fuel required in other parts of Britain. The woods around the Plant fall sick and die with poison. People, too, will be affected by the waste from this Dante's Inferno.

Factories are thriving on the Hirwaun Industrial Estate - G E C, Hitachi, Morgan and Brace, Dunlopillo, for example - and they become one of the main sources of employment as the mines fall silent one by one, pit wheels are stilled and rails rust. The slums are demolished or owners given grants to modernise them. Council housing estates are being built with modern conveniences such as indoor toilets and bathrooms. The little row at Greenfach is demolished as is the Green Dragon pub in front of it. A large library of concrete and glass is also built on this site.

The first supermarket to come to Aberdare, Fine Fare, has opened its doors in Commercial Street and so begins the decline of the small grocers' shops.

In

October, 1966, in another valley, a coal tip slides down a mountainside and

wipes out a generation of children. The Government now orders all tips to

be made safe. In Cynon Valley, waste tips are being levelled over the mountainsides,

spread with guano and reseeded.

It is 1972 and the Dare Valley Country Park is created, the first country

park in Wales and the first in Britain to be created from reclaimed colliery

land.

Prestigious new housing is being built throughout the valley from Woodland

Park in Penderyn to Sierra Pines in Mountain Ash. Out-of-town superstores

have replaced town centre food shops and the old corner shops are now flourishing

discount stores open long hours every day, run by the valley's newer immigrants

from Pakistan and India.

Of the Workmen's Halls, few remain. Nixon's in Mountain Ash and the Aberaman

Hall are razed to the ground by fire.

The Phurnacite had shut down, its chimneys blown up in a spectacle that drew

the crowds far from and wide.

The Coliseum is given a new lease of life as a cinema as well as theatre and

undergoes a complete refurbishment.

The walls and winding house of the Gadlys Iron Foundry is preserved and incorporated

into the Cynon Valley Museum.

The statue commemorating Caradog's choral victories has seen many changes

in Victoria Square in Aberdare's town centre. The latest refurbishment, prior

to the year 2000, saw the town given a flavour of its Victorian past.

The

morning sun has risen above the Abercynon Ridgeway, flanking the valley floor

as it leads through Mountain Ash towards Abercynon where the river Cynon meets

the larger Taff. The countryside is greener than it has been for many a long

year. The great woodlands of centuries ago are gone forever but new, smaller

woods are being planted to replace the trees wiped out as man, agriculture

and industry left its mark on the valley.

In Aberdare, the oaks rustling around the spire of St Elvan's church launch

their colonies of rooks and jackdaws morning and evening so that they orbit

like satellites around the landmark spire. St John the Baptist's church dozes

quietly, brooding in its Norman antiquity.

Across the town the new bus shelter reflects Victoriana. Pink-hued lamps dip

their heads modestly and there is a new clock on top of the bus shelter to

rival the one on St Elvan's spire that reads ten past six whatever time it

is.

Only one mine remains now - Tower - the last of the deep mines of South Wales.

On the verge of closure it was bought by its own workers and is thriving:

it is the stuff of stories. Much of the industrial history of Cynon is still

visible in the landscape. There are grassed-over tips, outcropping coal seams,

the twisted remains of rusted rails and, half buried in a stream, a buckled

dram.

The

stone bases that held the wooden stanchions are all that is left of Brunel's

viaduct that carried the Vale of Neath railway through what is now Dare Valley

Country Park.

Many of the hillsides that once were covered in trees, then in pit waste,

are now covered with new houses that push back the frontiers of the countryside

ever further.

The former railway lines are footpaths - the mineral line between Hirwaun

and Penderyn is now a walk called the Arcway, the Cwmdare-Cwmaman line is

a three and half mile walk between those villages.

Cascading along the contours of the hillsides are Cynon Valley's terraced

houses, higgledy-piggledy streets twisting and turning this way and that to

follow the contours of the land, seemingly defying gravity as they soar up

and down the steepest of hills. Now flamboyant with colour, they epitomise

this and all the other valleys of South Wales. Even their back lanes are treasure

troves of interest with a hotch-potch of doors, walls and fences, sheds, garages

and extensions.

In Mountain Ash, one row of houses that climbs the hillside has backs that

face the road. In an amazing array of zig-zagging steps and teetering, single-brick

pillars the back porches rise high above their gardens. Archways, doors, cellars,

washing lines and a carnival of brickwork seem suspended in nothingness, as

if a gust of wind would bring it all down. An old tin bath hangs on a wall,

geraniums blaze on balconies and large, sleepy cats sit as comfortably on

the edge of the precipitous drop as if on verandahs overlooking the Mediterranean.

The style of architecture owes nothing to any School but everything to all

things eccentrically Welsh - valleys-Welsh.